The construction of Catspaw began in the driveway of our one-acre home in South Miami in 1966. We had purchased this home because it was set back from the road, was in an area heavily wooded with pines and saw palmettos, was adjacent to multiacre homes on the south and east and adjacent to several vacant one-acre lots on the driveway side to the north, and had a two car carport that I could convert into a wood shop. (If ever there was a situation in which one could construct a sailboat hull in his driveway with minimal impact upon his neighbors, this was it!)

After enclosing the carport and building a shop, I laid out the station lines for Catspaw, full scale, on a ground level plywood platform in one corner of this shop. (I did not have sufficient room in the shop to also lay out any longitudinal lines, so I had to accept the offsets from the scale drawings, which I tried to make as consistent as possible.)

I was fortunate at the time to have the friendship and guidance of Jake and Else Van Hoek, whom I had met through Jean Filloux, a fellow student at Scripps. Jake had recently acquired some commercial property on the New River in Fort Lauderdale and was in the process of constructing a boatyard and marina there (New River Marine). Through Jake, I was able to order several thousand board feet of 4/4 in rough cut Philippine mahogany and an assortment of various sizes of other varieties of mahogany and white oak, with which to begin the construction of Catspaw.

I pieced together some rails in the driveway to support the upside down construction of Catspaw's strip planked hull and began assembling the spruce molds that would determine its shape. (I had figured out a way of transferring the station lines directly from the full scale drawing to these molds.) With the molds in place on the rails, Catspaw was beginning to look lke a sailboat.

Next I constructed Catspaw's sternpost and transom. This gave me my first experience laminating structural members (the transom beams) and my first experience with strip planking. (The transom was planked vertically, without the concave/convex shaping employed elsewhere.)

After constructing the inner framework for Catspaw's three bulkheads and adding the transom and bulkheads to the rails, I added the keelson (a fir 2 by covered with a 3/4 in white oak cap), the stem (multiple 3/4 in fir strips), and the clamp (multiple 3/4 in Philippine mahogany strips), laminating all in place using resorcinol glue. I also added the dead wood framing the propellor aperture and the deck beams, form laminated in the shop from multiple 3/4 in Philippine mahogany strips.

At this point I could begin the actual strip planking, starting at the bulwark cap and working up past the clamp towards the keel. This planking was tedious and took over a year to complete (working evenings and weekends). The 1 in by 1 in planks were ripped from the rough lumber using a table saw and the rough faces of the plank shaped with this same table saw, convex on one side and concave on the other. Each plank was attached in sections, butted at an angle (with a hand saw cut along the joint to insure a good fit). These sections were glued with resorcinol glue and fastened edgewise with galvanized nails extending through the adjacent layer of planking into a second layer. Twice during the buildup of the hull, a new line was cut in the existing strip planking to slow its advance towards the keel at the aft end of the boat.

One day towards the end of this phase of the construction, we received a note from building and zoning saying that someone had complained about the ongoing construction. I surveyed the neighborhood and could find no one who was upset by Catspaw's presence. Indeed the complaint had come from the lady from whom we had purchased our home, who also happened to own the two vacant lots to the north, which she was now trying to sell. We agreed to move the boat into the backyard behind the house (where it would not be so visible from the road), but not before the hull had been fiberglassed, at which point it could be turned rightside up and relocated.

This agreement put additional pressure on the construction schedule. It was now important to accomplish the fiberglassing of the hull in good time. I was already leery of undertaking this step on my own because I had no experience with fiberglass. Unfortunately, epoxy resin was new, and people in the polyester fiberglass layup industry didn't know how to work with it either. I made a bad decision and engaged a crew from a local fiberglass boat construction company to come one weekend and start the layup. By Saturday afternoon it was clear that they didn't know what they were doing. I told them to go home, and I started cleaning up the mess!

I next turned to a pair of fiberglass specialists from Jake's marina. They drove down from Fort Lauderdale daily and, gradually and systematically over the next two months, built up an epoxy fiberglass sheath encasing Catspaw's hull.

For some unknown reason, however, this second attempt at laying up epoxy fiberglass was also problematic. For years thereafter, I was plagued with having to patch local delaminations of the outer layer of fiberglass cloth. Each haulout would reveal one or two such delaminations. Fortunately, this problem gradually disappeared. Catspaw's fiberglass sheath has been stable for the last ten to fifteen years.

Behind the house (under an awning to keep out the rain and sun), I added some white oak frames (laminated in place), built Catspaw's two-layer fir plywood deck, and covered this deck with a layer of heavy fiberglass cloth (using polyester resin). I then built up the strip planked sides of the deckhouse and cockpit and covered the deckhouse with a temporary roof. (I wanted to mount the engine before permanently roofing this house.)

I had one more task to complete in Miami. I wanted to add a lead shoe external to Catspaw's built down keel. I constructed a form for the shoe and had it poured at a local foundry, an adventure all its own. The first pour was another disaster. The second pour into a second form went much better, and somehow I managed to lift Catspaw's hull, slide the shoe underneath, drill matching holes for the keel bolts (1/2 in threaded monel rod) through both the keelson and the shoe (recessed on the underside of the shoe so that the retaining nuts were flush with its bottom surface), and fasten the shoe to the keelson in snug watertight fashion, with the upper ends of the keel bolts extending well up into the built down cavity of the keel.

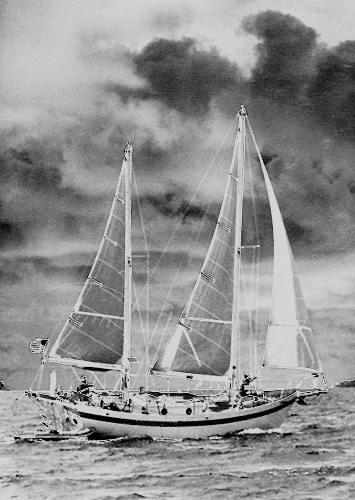

Photoshopped Catspaw on the wind in Tonga - 1

I had decided to leave my faculty position at the University of Miami's Rosenstiel School and join the staff of a new Oceanographic Center afilliated with Fort Lauderdale's Nova University. We had found a new home on a canal in Fort Lauderdale for ourselves and for Catspaw. But she would first have to spend some time in Jake's yard on the New River.

The trip north to Fort Lauderdale was still another adventure. Catspaw was picked up behind our Miami home, cradle and all, and dropped onto a low bed trailer. We then proceeded in caravan towards Fort Lauderdale, truck and low bed, I, watching the low bed for signs of trouble, and the crane, which would be needed at New River to deposit Catspaw and cradle in a corner of the yard. (There may also have been a police car or two, as Catspaw was undoubtedly a wide load.)

Everything went fine until we arrived at the entrance to the yard. But there was a sharp turn in the yard's narrow entrance, and the low bed could not negotiate it. We could not get into the yard to deposit Catspaw. What now?

Jake to the rescue! We would drop Catspaw and cradle into a neighboring canal, tow her around to the yard, pick her up out of the water, and drop her back ashore, where she was supposed to go in the first place. And so we did! The only real surprise was that in the water, Catspaw, only partially ballasted, had two stable points, one listing about 40 deg to starboard and the other listing about 40 deg to port. (But the list was symmetric and she didn't leak!)

At New River Marine, I proceeded to pour the inside ballast, a reinforced concrete member that filled the built-down keel from mainmast to sternpost, made heavier by a central basket filled with reinforcing rod cutoffs. Integrated into this member were bolts to anchor the mast steps and to anchor a (galvanized) rectangular angle-iron frame under the engine, providing a support for the engine beds and a sump for any fluids that might eventually leak from the engine.

For an engine, I had acquired a Starrett 121D (a marinized version of the Isuzu DL201 truck diesel). It fit in the space available and was reasonably priced.

I next bolted a pair of white oak engine beds to the engine frame and lowered the engine onto these beds through the open deckhouse. It would be a while before I would be able to start up the engine, but I could begin to install it.

First on the agenda was the shaft. I acquired a suitably sized used bronze propellor from Ona, in the yard at the same time, bought some bronze shafting and a pair of bronze stuffing tubes, and proceeded to cut a hole for the shaft in the deadwood, mount the opposing stuffing tubes, one inboard and the other outboard in the propellor aperture, install the two-section shaft, mount the propellor, and roughly align the engine.

At about this time I undertook an assortment of other tasks. I laminated a fir rudder, overlayed with fiberglass, and hung it from the transom and sternpost, using some heavy duty stainless hardware I machined on the lab's Bridgeport milling machine. (It was remarked that I could hang the entire boat from just one of the hinges!)

I also laminated a white oak tiller and some white oak mooring cleats. And, after cutting holes for the chocks in the bulwark, forward, aft, and amidships, and lining these holes with some bronze chock fittings, I throughbolted matching cleats to the inside of the bulwark (a single cleat each for the fore and aft chocks and a pair of cleats for each midships chock).

The yard also helped with a number of tasks. Fore and aft plywood panels were added to the three bulkheads, and the interior skin was sanded smooth (a nasty job I was happy to give to someone else).

After about a year on the hard, Catspaw was given several coats of bottom paint, launched, and tied up under a high shed in the yard, where a two-layer plywood roof, fiberglass covered, was added to the deckhouse. In the water for the first time since pouring the inside concrete and mounting the engine, Catspaw was no longer listing, but it was clear that she needed additional ballast. She was hauled back out of the water and two additional side slabs of lead were added to her external shoe (lagged into the shoe and bolted laterally through the overlapping keelson with stainless threaded rod). Additionally, a substantial quantity of inside lead was attached to the bilge at the forward end of the saloon.

At this point Catspaw was relaunched and towed home to our dock, where I could more conveniently tackle the innumerable tasks remaining before she would be ready to go cruising. Here are some of the tasks completed over the next few years, most at the dock, some in subsequent haulouts, and not necessarily in this order:

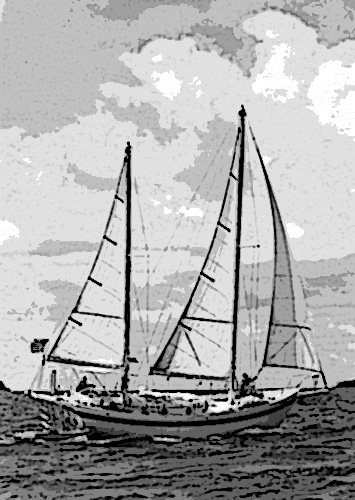

Photoshopped Catspaw on the wind in Tonga - 2

Although far from complete, Catspaw was finally becoming somewhat operational, and the temptation to take her somewhere was becoming unbearable. (I personally think that, in pursuing such a long term project, it is psychologically important to get some reward from this project before it is fully complete. How many similar projects have eventually been abandoned because the builder demanded perfection before taking advantage of his creation? Indeed, perfection is often an illusion. It is in exercising an imperfect creation that one learns what is necessary to perfect it.)

In characteristic fashion, on our very first attempt in 1971 to take Catspaw out to sea, we picked up a plastic bag in the intake and had to return to the dock to clear it. The following day we were more fortunate and made it out through the port past the breakwater without incident. (On our next haulout, I installed screens over all intakes.)

We continued on, under sail, to Miami and Biscayne Bay, anchoring for the night behind Key Biscayne. (We were chased from our first anchorage because it was too close to the Nixon compound!) The next day we sailed around a bit in Biscayne Bay at various angles to the wind and then headed back north to Fort Lauderdale and home. Not of itself a very memorable excursion, but one that held promise of other memorable excursions to come. We were finally on our way!

An occasion to test Bahama waters came in August of 1972 in connection with one of several field projects I had been conducting in the Bight of Abaco, Bahamas. Catspaw would basically provide accomodation for several people while they worked from the Oceanographic Center's vessel Gulfstream at a research tower previously erected in the upper Bight. We sailed across to West End, crossed the Little Bahama Bank north of Grand Bahama Island to Cave Cay, and entered the Bight at Spence Rock. After rendezvousing with Gulfstream and subsequently completing our work at the tower, we returned home to Fort Lauderdale via the Berry Islands and Bimini.

We were ready for something more challenging. Although we were still without refrigeration and a hard dinghy, relied primarily on the engine to recharge our batteries, and were looking at a long hard slog to windward, we decided to head out through the Bahamas and down into the Carribean. Jody's brother Jay, who had been with us for several months, helping with Catspaw's interior, would accompany us as far as Georgetown. We departed Fort Lauderdale April 2, 1973.

After clearing into Nassau and spending a few days in various pursuits there, we crossed to Allen's Cay and continued, in short hops, down the Exuma chain towards Georgetown. I had not been in the Exumas since the fateful summer of 1959 (that had turned my life around). That summer, however, I had been on a vessel drawing only 3 ft; to my delight, I found that 5 ft could still navigate many of the channels and, in concert with an inflatable, provide access to just about everything of interest. I remembered the Exumas as a very special place. It was now a little less remote, but still very beautiful and still very special.

From Georgetown on, we knew it would start to get difficult. The hops would be bigger and the wind fresher. So we lingered a bit at Stocking Island to savor the moment (and to see Jay off and welcome another friend, Doug Stover, aboard) and then headed out around the northern tip of Long Island, down past Crooked Island, Fortune Island, and Castle Island, on our way to West Caicos.

South of Castle Island, it became a rough slog, 20 kts on the nose. And after a while, we didn't know precisely where we were any more. GPS had not yet appeared on the mass market, handling a sextant was difficult under these circumstances, and dead reckoning is just not very reliable on the wind, particularly if there is an unknown current. We were pretty sure we had cleared Hogsty reef, but we didn't really know how close we were to Caicos.

Three days out of Exuma, we spotted land to the south southeast. It proved to be the island of Little Inagua. We approached and anchored in the lee. It was a rather hostile and alien shore. The beach was cobblestones, there were coral heads, and it was difficult to find a good spot for the anchor. We could hear wild donkeys in the scrub. The next day we went fishing close by the boat and had tremendous luck (until the sharks came!).

By nightfall the wind had moderated somewhat. As much as I would have liked to stay another day and further explore Little Inagua (perhaps there were flamingos?), we decided to move on to Caicos. We set off and, late the next afternoon, we again spotted land. The following morning we entered the Caicos Bank south of Providenciales.

After a week in South Caicos, we continued on to the north coast of the Dominican Republic. For the first time we were sailing in largely unprotected waters and for the first time we had green mountains to point the way. And, as rough as the crossing to Puerto Plata had been, coming out of Puerto Escondido, we were handed a stroke of good fortune. As we were considering where to go next, the wind gradually dropped to nothing. Indeed, we were subsequently able to motor almost all the way from Puerto Escondido on the north coast of the Dominican Republic, across the Mona Passage (which can be very rough), to San Juan on the north coast of Puerto Rico.

In San Juan, we were met by my brother Noel and his wife Helen, who were living in the Luquillo rainforest on a project to investigate the natural history of the Puerto Rican parrot. I needed to return to the US for several weeks to deal with some issues at our lab. In the meantime Jody and Garth would move in with Noel and Helen, and Catspaw would sit on a mooring in San Juan Harbor. (Doug also flew back at about the same time I did.)

I don't know what manner of creature it is that grows in San Juan Harbor, but when we subsequently went to put Catspaw's engine in gear in order to motor away from the mooring, there was no forward thrust whatsoever, none, nada! A swim revealed that the propellor was now massively fouled with some sort of calcareous growth (this after just under a month in the harbor). Sometimes I wish that all engine problems could be solved by spending a half hour in the water with a putty knife!

We next moved on to the islands of Culebra and Culebrita (a very pleasant stop) east of Puerto Rico and, from there to the US and British Virgin Islands, spending two weeks in the vicinity of St John's (we particularly enjoyed Cruz Bay, Norman Island, and the Baths on Virgin Gorda), before setting off across the the Anegada Passage to St Maarten. It was our last true beat to windward and we were glad to put it behind us. (We would still be close-hauled for a while, but the tacking would gradually disappear as we worked our way further south.)

We were now moving fairly rapidly from one island to the next, intent upon getting down to the heart of the Lesser Antilles, Dominica, Martinique, St Lucia, St Vincent, the Grenadines, and Grenada, before it got too late in the summer. Grenada was supposedly relatively safe. (In 2006, however, a friend of ours was anchored on the south coast of Grenada when hurricane Ivan roared through. He was fortunate. His boat was not blown out to sea, but grounded on a soft bottom and escaped essentially undamaged.)

In St Barts, we bought Mount Gay Rum for under $1 a bottle, in St Kitts, visited the Brimstone Hill Fort overlooking the island and the neighboting island of St Eustatius, in Nevis, tasted genips for the first time, and in Deshaies, Guadeloupe, found a young girl who had never heard of the United States of America. She knew about Canada, however (where they speak French).

In Guadeloupe we were joined by our friend Jan Witte, who would be with us until Martinique. We took a bus to Basse-Terre and another to St Claude, and walked up the mountainside towards La Soufriere, but it was misted over, so we did not continue to the top.

On to the Saints, Dominica, and Martinique, accompanied by the Watergate hearings, broadcast in real time by Armed Forces Radio. Jan and I had a different view of what was going on, so our discussions were often lively. It was somehow very satisfying to be sailing along some foreign shore in your bare feet and yet be privy to history in the making.

Behind these high volcanic islands, the wind was very light; in the passages between islands, it was roaring. But we were no longer close-hauled; we were close reaching. And the passages were short enough to get across in well under half a day. Typically, we set off in the morning with working jib and reefed main. That was usually more than enough.

We stopped for only a few days each in Dominica, Martinique, St Lucia, and St Vincent, as we were anxious to get further south and expected to more fully explore these islands later in the summer with Helen and Noel. We did stop overnight at Anse des Piton on St Lucia (a very memorable anchorage), and we did relax for a couple of days at Young Island before crossing to Bequia and the Grenadines. In the Grenadines we stopped at the Tobago Cays for a day and a half and snorkelled the impressive Horseshoe Reef. (Unfortunately it was quite windy, and the visibility was not that good.)

We had arrived in Grenada. It was the very end of August; in another week or so and it would be the peak of the hurricane season. We needed to remain in the vicinity of Grenada for another couple of weeks (so that if a storm threatened we could quickly find safe harbor somewhere south of its expected path), and then we could slowly start making our way back north.

After three nights in St George's Harbor, we made our way via Prickly Bay to the Hog Island anchorage, a supposed hurricane hole on the south end of the island. It was very windy, windy enough, in fact, to lift and overturn our Avon inflatable, tied astern with its Sea Gull outboard attached. I retrieved the outboard, took it apart and soaked everything in kerosene, and did my best to dry things out before putting it back together. It would not start.

The next morning it did start. I thanked my good fortune and put it back on the Avon. Ten minutes later, the wind again overturned the dinghy. Well, I thought, this may be a hurricane hole, but it sure is windy in here!

Second time through was a charm. The outboard started right up, and this time I declined to put it back on the Avon.

After several days at Hog Island, we turned around and slowly started back north, revisiting the Grenadines with Lex and Sylvia Brincko. Noel and Helen joined us in St Vincent. We rented a car and drove up the east coast, with its black beaches, to a coconut plantation on the slopes of the volcano at the north end of the island. A trail lead from this plantation to the top of the volcano, a most spectacular vantage point. At the time, a colorful lake lay several thousand feet below at the base of the caldera, surrounding an interior peak. (I understand that the volcano has since erupted, so the current view may be quite different.)

In St Lucia, Noel and I spent an overnight in the forrest near Marigot Bay, looking for parrots. In Castries, Garth had his sixth birthday. All I could find for ice cream was a 2 gal container of chocolate, so we all had multiple helpings and then invited the local kids in the anchorage to help finish it off. We spent the afternoon sliding down our upended Avon from the boomkin into the water.

In Martinique and Dominica, we again looked for parrots, and near Roseau, Dominica, swam in Titou Gorge. The hot springs just outside the gorge were particularly welcome to a crew unaccustomed to bathing in hot fresh water.

Following Noel and Helen's departure, we continued on to English Harbor, Antigua (via the Saints and Guadeloupe). We threaded our way into the inner anchorage and dropped our hook. On a nearby boat we spied a towheaded girl about Garth's age. It was Katie Alcard, daughter of Claire and Edward Alcard, well known sailor and author. Claire has since authored a book of her own on living aboard with kids. The frontispiece of her book is a photo, taken by Jody, of Garth and Katie on Catspaw's bowsprit.

Shortly after arriving in Antigua, we were threatened by a tropical storm. Fortunately, it passed us by.

From Antigua, we sailed on to Saba, a quaint and colorful island community originally settled by the Dutch. For the first time we were well off the wind, and I remember playing with sheet to tiller steering (with mixed success). We rounded the northwest corner of the island and tied up to the small commercial dock lining the inner edge of the breakwater. Sometime later, ashore in the Bottom (at the bottom of an ancient volcano), we were rousted back to the dock. A small freighter had come in to port, and we needed to get out of the way. (We tied alongside the freighter.)

In returning home, we had decided to follow the southern coasts of Vieques, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola. Following a brief stay in St Thomas, we sailed on to Vieques and Puerto Rico, stopping in a lovely bay on the south coast of Vieques, in a not so lovely but spectacularly bioluminescent bay on the southeast coast of Puerto Rico, and in Ponce.

We started across the Mona Passage towards the Dominican Republic. At Mona Island, we stopped and found a reasonably snug anchorage inside the reef on the west side. We had instructions on hiking from the beach to a cave on the western edge of the plateau somewhat to the north. We set off and were pleased to eventually find this cave. (It wasn't Carlsbad, but how many caves are? It was quite extensive and had both stalagtites and stalagmites. What more do you want?)

We stopped twice on the south coast of the Dominican Republic, once in Santo Domingo to pick up Bob Long, who was to join us until Port au Prince, Haiti. In both cases the long arm of the Dominican military was evident. In Santo Domingo, Catspaw was tied to a commercial dock under military guard (for our protection), and, in the other bay further west, the officer explained in German that we would have to spend the night alongside a Dominican Navy vessel. (We didn't speak Spanish, and he didn't speak English.)

Somewhere along the south coast of Haiti, we hooked into a large wahoo. We were not, however, equipped to land such a large fish. While we were discussing how we might possibly get him aboard, he broke loose and swam off.

We were approaching Jacmel, our next destination. But when we went to turn on the engine to enter the port, it wouldn't start. I had a pretty good idea that the problem lay with the injector pump, because I had heard that Starrett's scheme for mounting the raw water pump on the injector pump shaft, separated by a seal, would eventually give trouble. Indeed this seal had now leaked water into the pump. The engine was done for the duration of our cruise.

Without an engine it would be difficult to get in and out of many of the ports and anchorages we planned to visit on the way home. Prudence dictated a radical change of itinerary. We would skip Haiti altogether and sail more or less directly home, with a single stop in Great Inagua (to rest and to allow Bob to call Barbara and let her know that he would be returning with Catspaw instead of flying home from Port au Prince).

We proceeded west along Cape Dame Marie and then north through the Windward Passage to Great Inagua. (As the anchorage off of Matthew Town is an open roadstead, there was no problem getting in and out without an engine.)

The uneventful downwind leg from Great Inagua to Fort Lauderdale was our longest passage ever and a foretaste of the many extended downwind passages we would make in our trip around the world in the early 1980s. We had the advantage that there were three of us to keep watch. But we had to continually steer the boat. With only two, it would have been a significant long term strain. We clearly needed to install some sort of wind vane steering.

From Great Inagua, we proceeded east along the Old Bahama Channel between Cuba and the Great Bahama Bank, eventually crossing onto the bank near Cay Santo and, after several days of more comfortable bank sailing, exiting back into the Straits of Florida south of Orange Cay.

Arriving in Port Everglades, we pulled up in the lee the Oceanographic Center and anchored. Presently, Willie Campbell came out in a skiff to greet us and tow us into the lab basin, where we remained until the new year. Catspaw had successfully completed her first extended cruise in foreign waters, much of which had not been easy, and had successfully weathered her first major crisis.

Photoshopped Catspaw on the wind in Tonga - 3

Back home following our Carribean adventure, I struggled to resume a number of projects underway at the Oceanographic Center. Simultaneously, I worked to restore Catspaw's engine to operational status and to address other aspects of her continuing construction.

The first order of business was to fix the injector pump. I removed the pump and took it to a local diesel shop. A week or so later I had it back. I remounted it, but could not get the engine to run. The shop had configured it for the wrong rotation! Several days later, I had it back for the second time. This time the engine ran, but poorly. I adjusted the timing and found that I could get it to run smoothly if I slipped this timing one cog. (As seen through the observation port on the forward end of the engine, the marks now failed to nest by one cog.) I was never able to get an explanation of this anomaly out of the diesel shop, but I was happy to have the engine running again and did not press the issue.

Concurrently I labored to insure that this particular problem would not occur again. Mounting the raw water pump on the injector pump shaft separated by a seal was just asking for trouble. Also I had been having problems with temperature regulation and wondered about the pump's size. I settled on a somewhat larger replacement, a 1 in Oberdorfer pump (for a Palmer engine), that could be bracket mounted on the starboard side of the engine and cog belt driven from the injector pump shaft.

A pending field experiment at the Bight of Abaco tower site in November of 1974 provided the opportunity to test these changes.

Dave Hunley had designed and welded up five very substantial support stands for some microbarograph instrumentation to be employed in the experiment. (Monitoring very small fluctuations in air pressure close to the water surface is key to understanding how the wind grows waves.) Prior to the experiment we needed to deliver these stands to the tower site.

In mid August, we set off in Catspaw for the Bight of Abaco. Aboard were Bob Long and his family. Gulfstream would follow a few days later, towing the stands in a makeshift barge. After rendezvousing at Basin Harbor Cay, we would dump the stands overboard, one by one, and use some surface flotation and a comealong to right the stands and place them on the bottom in a configuration appropriate to the experiment.

Following field operations at the tower, the Longs returned home with Gulfstream, and we picked up Linda Smith on the back side of Cooperstown, Abaco, and exited the Bight to the northwest via Spence Rock and Cave Cay. We then briefly visited several of the Abaco cays to the north before returning home to Fort Lauderdale via West End. (We loved the inner anchorage at Double Breasted Cay but were chased out of Grand Cay by noseeums.)

In November we returned to the Bight with Catspaw. Aboard were the Canadian researcher, Fred Dobson, and his family. (Fred, Bob Long, and Jim Elliott were co-investigators in the project.) The Dobsons would set up camp on Basin Harbor Cay for the duration. Bob and Barbara would arrive on the Bellows, Nova's second research vessel. The Bellows would provide a platform for operations at the tower site (diving operations to mount instrumentation and survey its spatial configuration, laying of cables necessary to power this instrumentation and record its output, acquisition of data, and housing and feeding those involved in the experiment). As ragtag as this project may appear to have been, the Bight of Abaco experiment is widely recognized as having made a significant contribution to the current understanding of the generation of waves by wind.

The following summer, we again took Catspaw across to the Bahamas, entering at Great Harbor Cay and spending a late afternoon and evening on our side in Little Harbor (it's very shallow in there, with just a few holes that will carry 5 ft at low tide) before crossing to Nassau. We returned home via Lyford Cay and Goulding Cay at the northwest corner of New Providence, and Middle Bight, Fresh Creek, and Morgan's Bluff on the east coast of Andros.

Sometime during this period I started putting together an engine driven refrigeration system for Catspaw. We had thus far done without refrigeration, but clearly it would greatly improve our cruising life to have a not so occasional cold drink and to be able to keep leftovers for the next day. With home canning in the picture, I didn't think a freezer section was that impotant; I would be happy with a refrigerator only. (There are few things more disheartening than losing a whole freezer full of food because of some mechanical or electrical failure.)

At the time, I didn't think that an off the shelf 12 VDC system would work out too well because, other than running the engine, I didn't have a good way to reliably and rapidly recharge the batteries, (This option is clearly more acceptable nowadays, because of the availability of more efficient wind generators and large reasonably priced solar panels.)

I built a top-loading PVC icebox into the counter on the starboard side of the galley (aft of the chart table), insulated it all around with 3 in of polyurethane foam, and machined and silver soldered the core of a large holding plate to go inside (with 3/8 in brass top and end plates and 5/8 in schedule K copper tubes running back and forth between the end plates). I then found someone to solder a heavy brass skin around this core. I now had a holding plate with a capacity of roughly .5 cu ft (in an icebox of roughly 3 cu ft). I would fill this plate with water, leaving some air space at the top, and hope that its construction was robust enough to stand the repeated freezing and unfreezing of its contents (as it has).

I acquired a York compressor from an auto airconditioning shop and other components (control panel, expansion valve, reservoir, and monel water-cooled condensor, all rated at about 1 ton) from a refrigeration supply house, and put everything together, mounting some components along the starboard edge of the engine room and others on the aft bulkhead on the starboard side.

The resulting system has worked well for us. We typically charge the refrigerator at relatively low 1200 RPM for about an hour every other day. We would prefer if it were less, but an hour every other day isn't too bad.

Also during this period, I saw a small fiberglass dinghy built by Brandon Manufacturing, located (at the time) just west of Port Everglades (behind Lester's Diner). It was very light, barely 8 ft in length, and came with a cat sailing rig. We had been thinking that a second hard dinghy to complement the inflatable would be a good addition, and this looked to be the right choice. It was not long before we had a Jolly Boat and were figuring out where and how to stow it on deck.

In fact the Jolly Boat stows very neatly upside down over the forward hatch. An aft rail on deck just forward of the mainmast supports and pins her transom; her bow locks into a support built into the bowsprit. This arrangement does compromise to some extent the handling of Catspaw's headsails, but it means that one can leave the forward hatch propped open most of the time (even underway), improving the air circulation below deck.

In November 1976, Jody gave birth to our second son, Gavin. The following spring we introduced baby Gavin to Catspaw by taking him along on a trip to the Abacos. Also along on the trip was a Fuji super-8 camera that would eventually accompany us around the world.

Entering at West End, we proceeded across the Little Bahama Bank to Great Sale Cay, the Carter Cays, Allan's Pensacola Cay, Powell Cay, and Green Turtle Cay. My folks joined us in Green Turtle and subsequently had the misfortune to experience the Whale Cay passage south to Geat Guano Cay and Man-O-War Cay on a particularly rough day. It is perhaps indicative of grandma's distress that she threw up on baby Gavin.

After seeing grandma and grandpa off in Marsh Harbor, we returned home via Hopetown, the Pelican Cays, Frozen Cay, Chub Cay, Gun Cay, and Bimini.

Following the Abaco trip, I produced my first super-8 movie, "Abaco or Bust," from the Fuji footage. How I wish present day digital camcorders had been available at the time.

We had decided to take Catspaw around the world starting in 1980. It would be good timing for both Garth and Gavin. Garth could home school aboard Catspaw, but return in time for two years of regular high school before going off to college. Gavin would be too young for school and would return as a first grader. (It helped, of course that both Garth and Gavin were bright kids. Garth did in fact return for his junior and senior years and wound up as a presidential scholar finalist. Gavin was reading the Lord of the Rings well before he got back and, having returned, entered the second grade instead of the first.)

One major task remained and a multitude of smaller tasks. It would take the better part of a year to finish getting ready. It also occurred to us that most of the smaller tasks could be accomplished at anchor in the Bahamas as easily if not more easily than at home. Accordingly, we decided to break our ties with home in early 1979, a year in advance of our departure for Panama.

First I had to fit Catspaw with a wind vane steerer. Catspaw's ketch rig is not well suited to a commercial steerer. The most effective steerers employ a dual axis vane that articulates about a horizontal axis. There is not enough clearance between Catspaw's boomkin and mizzen boom to accomodate such a steerer, and the mizzen sheet is in the way.

I decided to look at John Letcher's book on self steering. In it there was the germ of an idea for a dual axis vane (with both axes vertical) that might be made to work for Catspaw. I settled on a basic design and started machining parts at the lab. Where I needed parts welded together, I got Dave Hunley to help. The steerer would drive a trim tab on the trailing edge of the main rudder through a series of linkages, one of which needed to be aligned with the axis of the rudder. I built the necessary linkages, delrin bearings, hinges, and a suitable trim tab, and put them all together, using some commercial bronze bushings and roller bearings to bear the considerable weight of the steerer's drive shaft (made heavy by two lead counterweights). Lo and behold, to my utter amazement, it worked. (Some photographs of the steerer are included on the Catspaw/Description page.)

I announced my intention to quit my job at the Oceanographic Center in early 1979, and we began looking for a tenant for our house. We found a local yacht broker to move in. It was a good match because she would have ample opportunity to discount her rental of the house by in turn renting out the dock to her many clients. (In fact we are quite sure she made out like a bandit, perhaps even clearing some profit from the enterprise. It's OK, Cynthia, we were happy to have had such a reliable tenant.)

Indeed we were Cynthia's first customer. The time came to turn over the house, and we were still packing. We moved everything that still needed to go aboard Catspaw to the back porch and rented our dock from Cynthia for a month, gradually loading everything aboard.

Towards the end of March 1979, we were finally ready to leave for the Bahamas. We departed Fort Lauderdale and eventually reached Allen's Cay in the northern Exumas (via Great Harbor Cay and Nassau). This would be our home for the next month while we addressed some of the remaining tasks on our list.

Shortly after our arrival at Allen's Cay, we made the acquaintance of Dan and Peggy Van Ginhoven aboard Osprey. Dan and Peggy were on their way to the Panama Canal and the Pacific. We would see them again several years later in Papeete and in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. (Dan and Peggy would greet us as we tied up in the low rent district of Papeete harbor, and Osprey and Catspaw would arrive in New Zealand the very same day. Indeed, Osprey would tow us into the dock at Opua.)

The Van Ginhovens and Osprey would later reach and settle for a while in Guam. Osprey, on the hard, would not survive a susequent tropical cyclone.

Another acquaintance from this period was the crew of Quickstep, Michael and Nancy Christie. Michael was an avid fisherman and a true gentleman. He liked going fishing with me because I didn't banter on about lots of extraneous matters. When we went fishing (usually in the Jolly Boat), we went fishing, period.

On one occasion he hooked into a a small shark on low test line. He was determined to land the shark. That meant playing it all the way back to Leaf Cay and beaching it. I ran the Sea Gull outboard and Michael played the fish, all the way in to the beach. We grounded the dinghy and hopped out to bring the shark the rest of the way in.

Unfortunately, I had what I would now call a senior moment; I pulled a little too hard on the line. Off went the shark ... all that effort for naught! And I was responsible. But in such moments a man shows his true character. To Michael, it was as if nothing had happened. (Perhaps it was the chase that was important. He had certainly handled that about as well as it could be handled. So what if I had screwed it up?)

Michael and Nancy later went on to the Virgin Islands for an extended stay. That's about where we lost track of them.

After much painting and varnishing, we sailed back to Nassau. (I had to fly back to Fort Lauderdale to attend to a number of things.) When I returned to Nassau, we set off for Spanish Wells and Eleuthera. Joining us were Garth's friend, Laci Nemeth, Laci's mom and our good friend, Evi, and her friend, Dick Norton.

Spanish Wells is one of those inbred Bahama communities where everyone has the same last name and looks alike. The fisherman of Spanish Wells employ relatively modern methods to acquire their catch, and, as a consequence, the community is comparatively well to do. (Fishing in their wake, however, tends to be rather unproductive.)

From Spanish Wells, we backtracked to the Current to gain access to the lee side of Eleuthera Island. I had spent some time in Givernor's Harbor in the early 1960s, acquiring data for my thesis at Scripps. Eleuthera is a good environment for ocean wave studies, but, because of the insufficiently vigorous tidal flushing, it is not particularly scenic. (As in the Bight of Abaco, the water tends to be cloudy, particularly after a blow.)

The region also offers little protection from the west. Hatchet Bay would appear to be an exception to this rule, but the holding inside is treacherous.

I had met two pioneer couples during my earlier time in Governor's Harbor. One was Ron and Aleda Turner, then captain and mate on the charter schooner Mystic. The other was David and Cazna (Anzac spelled backwards) Mitchell, who operated a small dive shop and vacation retreat in the cove just north of Governor's Harbor. Their precocious son, Marcus, perhaps five years old at the time, routinely commandeered a small Boston Whaler around the point to Governor's Harbor to pick up the mail.

Ron Turner later acquired the schooner Keewatin. As of May 2007, he was still chartering Keewatin out of Marsh Harbor. (Keewatin, by the way, had to be massively rebuilt following a hurricane that roared through Hatchet Bay some years ago.) Aleda is dead several years now. David and Cazna are probably long gone. Marcus is still thriving. He has his own private airstrip, owns several small planes, and has been active in marine salvage and construction. (He built Sampson Cay Marina.) To this day, he continues to leave his mark on the Bahamas.

Following a leisurely transit of the west coast of Eleuthera from Hatchet Bay to Rock Sound, we worked our way across the shallows to Powell Point, stopping at various heads to look for lobster, and then set a couse across Exuma Sound to Warderick Wells Cay. We would finish the summer at two of the most scenic destinations in the Bahamas, Warderick Wells Cay and Hawksbill Cay. We would then return briefly to Allen's Cay and, having gone full circle, head home via Nassau, the Berry Islands, and Bimini.

Back in Fort Lauderdale in mid August, we retreated to my parents' comfortable home in the Coral Ridge section of town (complete with hot shower and swimming pool) and looked for a secure berth for Catspaw for the remainder of the hurricane season. We found such a berth in the Citrus Isles. One storm, David, came reasonably close, but otherwise the season passed unremarkably.

Of particular importance to our well being in the coming months would be home canned meats, and we set about rebuilding our inventory. Mostly we used 1 quart Mason jars. They held too much for one meal, but, with refrigeration, we could make two meals out of each jar. We canned the jars, seven at a time in a large aluminum pressure cooker that we carried aboard.

Penn Dutch sold fresh hams at a good price. (Canned pork is virtually indistinguishable from fresh pork, and pork and sauerkraut was a favorite.) Beef, hamburger, turkey, and fresh fish also can well, sausage not so well. When you catch a fish on the open sea, it is invariably too big for a single meal. We quite often rolled out the canner underway to take advantage of a good catch. In American Samoa, we found turkey breast in the government market at a very good price and canned 30 lbs.

Garth had become interested in personal computers. He was daily visiting Radio Shack and playing with their new TRS-80. I resolved that one way or the other, we would depart home with a computer. The TRS-80 was not a good fit. It required too much power. I did some searching and found another unit, an Ohio Scientific C1P, that took less power and could be driven by an efficient off the shelf switching power supply. The C1P required tape input/output and had only 8K memory, but, coupled with a small Sears 12VDC entertainment center with tiny black and white TV screen and cassette tape transport, it would work. (Garth would later design games for the C1P using machine language, and together we would put together a Basic program to reduce my navigational sights.)

There were hundreds of details to attend to before leaving. Now was the time to go over the list and make sure that nothing was left unattended. A last haulout and, except for restocking last minute consumables, we were ready to depart.

Christmas, 1979, at my folks home in Coral Ridge was very special. Noel and Helen were there, my folks, Jody, Garth, and Gavin. No one said anything, but I'm sure that some, at least, wondered, was this perhaps the last time we'd be together?

Nah!